North in the Spring #24:

Fraser Canyon by John Neville

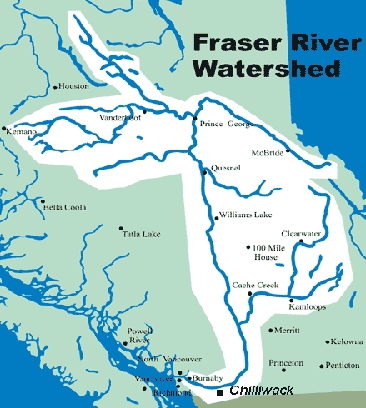

The mighty Fraser River "Qwu'uy" is 1375 km long. It starts with ice and snow, high in the Rockies. It flows through the heart of BC, the canyon and ultimately out to the sea. The salmon are the pulse providing life along one of BC's major arteries. The river drains a watershed covering about 1 quarter of BC's landmass.?This waterway is a web of life for millions of birds, animals and fish.?Being close to a Grizzly bear from horse-back in the Tonquin Valley; standing over a breeding tank of 2 meter long Sturgeon at Vanderhoof or witnessing 6000 Snow Geese coming in to land at Steveston; are just a few of the wonders I've experienced along this river.?

The Fraser Canyon Corridor is a scenic marvel and long ago an almost impassable barrier to travellers. First Nations have lived in the canyon for at least 9 000 years. When Simon Fraser travelled through: 1808, he was amazed to find ropes and ladders, made of vines and wood traversing the cliffs for local people. This allowed Nlaka' pamux trading between coastal people and those of the interior. After Mackenzie, Fraser, Thompson and other Europeans opened up the area to fur trading, other trails along the cliffs were developed. Fort Yale was constructed in 1847, below the rapids and quickly became a hub for the fur trade. For example, one horse pack train arriving in 1848 (from Kamloops) consisted of 400 horses and 50 men. The horses each carried two 41 kg packs of furs. The train was more than 1.75 km long and must have devastated much of the BC interior wildlife. In February 1858, Governor James Douglas sent a file of gold from the interior to San Francisco. It produced the desired reaction! By the summer of 1858, Hill's Bar near Yale was swarming with gold seekers. The gold dust and nuggets were washed downstream by the river and settled in the sand and gravel bars. Hill's Bar near Yale is also the highest point on the river that could be reached by paddle-wheeler. Emory Creek Provincial Park campground (where we stayed) was once a tent city of about 30 000 gold miners! Nearby is the pioneer graveyard where many of the miners were buried. In the late summer, Douglas arrived just in time, at Hill's Bar to settle a major dispute between American, Chinese and First Nation miners. At the end of 1858, miners found body parts of their comrades floating downstream. The young men of the Nlaka' pamux people took revenge after some of their young women were sexually abused. This became known as McGowan's war and was a very fragile moment for the young colony.  Hell's Gate near Boston Bar is perhaps the most dramatic point where the river cleaves its way through the Coastal Mountains. The cliffs are 1 000 m high above the raging rapids. In 1913 a fish ladder had to be built to help the salmon pass through after over-enthusiastic CN blasters caused a huge landslide. At various times of the year 3,475 m3/s of water is forced down the canyon. The turbulence in the canyon separates upper Fraser White Sturgeon from those in the lower river. The salmon need to be in prime condition to ascend through the turbulence on their final journey.

Hell's Gate near Boston Bar is perhaps the most dramatic point where the river cleaves its way through the Coastal Mountains. The cliffs are 1 000 m high above the raging rapids. In 1913 a fish ladder had to be built to help the salmon pass through after over-enthusiastic CN blasters caused a huge landslide. At various times of the year 3,475 m3/s of water is forced down the canyon. The turbulence in the canyon separates upper Fraser White Sturgeon from those in the lower river. The salmon need to be in prime condition to ascend through the turbulence on their final journey.

It is hard to contemplate the torment gravity creates in these rapids! The roaring turbulence, huge standing waves smashing against rock and cliff - no wonder it is called Hell's Gate. I have tremendous respect for this force of nature! About 10 years ago we rafted down the Blanchard and Tatshenshini Rivers in northwest BC. Kitted out in wet survival suits we felt safe from the fast cold river. The current carried us along at 24 km/hr and a standing wave raised us 3 m (almost vertical) in the air! At the crest of the waves water came over the bow giving us a cold slap in the face. The sunlight caught the droplets of water turning the mist into white spray. It was a thrilling, scary ride.  You can view the canyon easily along Hwy #1, between Hope and Lytton. The road was improved in the early 60's when 7 tunnels were blasted through. There are several good places to stop including Hell's Gate and some excellent First Nations' information panels. If you have a chance to ride the Rocky Mountaineer or Via Rail through the canyon in daylight its even more impressive. At Lytton, the road, CN and CP Rail and the communication towers move seamlessly into the Thompson River Canyon. What we call Lytton today lies on what was the Nlaka'pamux village of Kumsheen. The literal translation of Kumsheen is "where the rivers meet", but the name is more symbolic than that. It's more a metaphor for "the place in the heart where the blood mixes" - as in, this is the heart of the Nlaka'pamux nation. Between Hope and Lytton there are three bridges which give excellent views up and down the canyon. If you have the chance to cross the river in the Caribou there are some spectacular views of the northern Fraser Canyon. A back country gravel road leads from just north of Clinton, steeply down to a substantial metal bridge, crossing the Fraser. The road continues to the Churn Creek grasslands and the Gang Ranch. The bridge is the only man-made structure in the valley and you have a chance to see Golden Eagle and Mountain Sheep along the cliffs.

You can view the canyon easily along Hwy #1, between Hope and Lytton. The road was improved in the early 60's when 7 tunnels were blasted through. There are several good places to stop including Hell's Gate and some excellent First Nations' information panels. If you have a chance to ride the Rocky Mountaineer or Via Rail through the canyon in daylight its even more impressive. At Lytton, the road, CN and CP Rail and the communication towers move seamlessly into the Thompson River Canyon. What we call Lytton today lies on what was the Nlaka'pamux village of Kumsheen. The literal translation of Kumsheen is "where the rivers meet", but the name is more symbolic than that. It's more a metaphor for "the place in the heart where the blood mixes" - as in, this is the heart of the Nlaka'pamux nation. Between Hope and Lytton there are three bridges which give excellent views up and down the canyon. If you have the chance to cross the river in the Caribou there are some spectacular views of the northern Fraser Canyon. A back country gravel road leads from just north of Clinton, steeply down to a substantial metal bridge, crossing the Fraser. The road continues to the Churn Creek grasslands and the Gang Ranch. The bridge is the only man-made structure in the valley and you have a chance to see Golden Eagle and Mountain Sheep along the cliffs.

Whenever I travel along Hwy #1 through the canyon, I am awestruck by the tectonic forces and the movement of ice and water which have combined to create this dramatic cleft in the mountains. We are in the land of the Nlaka' pamux people, Spuzzum First Nation and the Sto:lo Nation who have enjoyed the abundance of fish and terrestrial wildlife for at least 9000 years. Driven by the fur trade and the gold rush, European diseases decimated the First Nations People. The Smallpox epidemic of 1862 was the worst. The way of life of the canyon was changed forever. Then the forces of a forest fire and an Atmospheric River, backed by Global Warming, swept across this landscape in June and November 2021. All the fragile parts of the road were swept away. 18 months later repairs are continuing. Just south of Lytton a marmot was lying sprawled on top of a concrete barrier watching us go by. Credit: Kevin Eastwood picture and quote Kevin Loring's Governor General's Award-winning play - "Where the Blood Mixes". |